Inhaltsverzeichnis

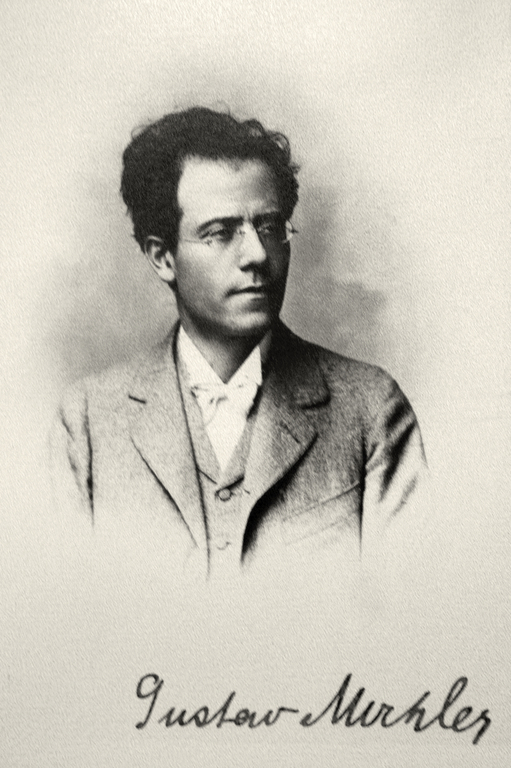

Gustav Mahler’s work is characterized by the tension between this world and the afterworld, between the earthly-natural and the spiritual-supernatural worlds.

Symphony No. 1

A trace of melancholy and painful beauty pervades Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. Mahler’s unmistakable tonal intonation is already completely formed in this work, and he was fully aware that he was charting new territory with his music. As he wrote to an old friend with regard to his Symphony No. 1: “You are probably the only one who will find nothing new about me here; the others will certainly be surprised about some things!” Indeed, the first performance, in 1889, after four years of work on the composition, was greeted by the public with boos.

Symphony No. 2

Mahler composed the Symphony No. 2 over the course of six years, completing the greater part of the work in the summers of 1893 and 1894 in Steinbach am Attersee. Mahler added soprano and alto soloists and a mixed choir, and used texts by the German poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, verses from “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” as well as his own poetry. Mahler himself reported that, after months of searching, the decisive inspiration came to him at the memorial service for the conductor Hans von Bülow. “The mood I felt as I sat there thinking about the deceased was so in keeping with the spirit of the work I was carrying around with me. The choir, in the organ-loft, sang Klopstock’s Resurrection chorale. It was like a flash of lightning, and everything became plain and clear in my mind! […] It is always the same with me: only when I experience something do I ‘compose’, and only when composing do I experience anything!”

The premiere performance, in 1895, which was financed completely by Mahler, was received poorly by the critics, but it was a resounding success with the public and sealed Mahler’s fame as a composer.

Symphony No. 3

Mahler’s Third Symphony, which he began in 1892 and completed largely in the summers of 1895/96 in Steinbach am Attersee, is in every way a monumental, intimidating work. The juxtaposition of disparate moods and various musical idioms gave rise to a wide variety of contradictory interpretations. Mahler himself characterised his Symphony No. 3 – and with it his entire symphonic oeuvre as well – with the words: “For me, a symphony means using all the technical means at my disposal to create a symphonic world. The constantly new and changing content determines its form by itself.”

Symphony No. 4

After his two preceding symphonies, Gustav Mahler again surprised – and perplexed – the audience in 1901 at the first performance of his Symphony No. 4. The work, which was composed at various places in Bad Aussee, Maiernigg and Vienna, appeared to be a complete departure from his previous symphonies: a turn of direction away from late-romantic pathos and toward a more classical formal language. Thus, the Fourth Symphony represents not only the culmination of the preceding symphonies, with their close ties to the poetry of the “Wunderhorn” songs; it also is a direct continuation, as the “epilogue in heaven”, of the Third Symphony. “It contains the cheerfulness of a higher world, one that is foreign to us,” wrote Mahler, adding, “and one that, for us, has something horrific and ghastly about it.”

Symphony No. 5

By 1901 Gustav Mahler had established firm work habits: during the year he worked as the director of the Vienna Court Opera, while in the summer months he devoted himself to composing. He wrote his Fifth Symphony in 1901 and 1902 in Maiernigg am Wörthersee, in the small “composing cottage” that offered the quiet Mahler required for his work. With the Symphony No. 5, Mahler for the first time wrote purely instrumental music, without using texts or poetry as a model. In 1902 he married Alma Schindler, and something of the happiness of these early years is reflected in the Adagietto, for strings and harp. Nevertheless, a deep fissure seems to extend through this work, with the contrasting moods clashing roughly and abruptly against each other. This work presented its composer with tremendous challenges. Right up until his death, Mahler continued to make changes to the score. But the demands Mahler made on his listeners were, as usual, also extreme. Following one performance, he made the resigned comment: “The Fifth is a cursed work. No one understands it.”

Symphony No. 6

“Wie gepeitscht” (“as if whipped), “Wie wütend dreinfahren” (“attack furiously”), “Wie ein Axthieb” (“like the blow of an axe”) were a few of the performance instructions Gustav Mahler wrote in the score of his Symphony No. 6, which he composed in Maiernigg in 1903 and 1904. There is ample evidence that Mahler intended this work to be his “classical symphony”; however, this composition, as well, ended up far beyond the horizon he had visualized at the outset. Of this symphony, Mahler said: “My Sixth will propound riddles the solution of which may be attempted only by a generation which has absorbed and truly digested my first five symphonies.”

Symphony No. 7

The concept that music is linked to dreams and the unconscious, and thus capable of expressing truths that lie beyond reason, is one that shaped the entire Romantic movement. But at times the music in Mahler’s Symphony No. 7, which he composed at the Wörthersee in the summers of 1904/1905, is more reminiscent of Goya’s etching “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters“. Nonetheless, from its deepest despair, the music always finds moments of transfigured serenity. The musician, wrote Mahler, is like a sleepwalker. “He knows not which path (perhaps along the edge of dizzying chasms) he is treading, but he follows the distant light, whether it is the eternally shining star or an alluring will-o‘-the-wisp!”

Symphony No. 8

In the summer of 1906 Mahler left for Maiernigg am Wörthersee “with the firm resolution of idling the holiday away and recruiting my strength. On the threshold of my old workshop the Spiritus creator took hold of me and shook me and drove me on for the next eight weeks until my greatest work was done.” The premiere performance of the “Symphony of a Thousand” was an event like none other before it in the history of the performance of his works, bringing Mahler his first great success since the performance of his Second Symphony. Mahler himself wrote of the work: “… it is the greatest thing I have ever created … Try to imagine the whole universe beginning to ring and resound. These are no longer human voices, but planets and suns revolving.”

Das Lied von der Erde

In a time of grave personal crises – in 1907 Mahler’s daughter Maria died, and that same year Mahler was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect – Gustav Mahler was determined to cheat fate himself. Beethoven, Schubert, Dvořák and Bruckner had each written only nine symphonies before they died, so instead of beginning work on a ninth symphony, Mahler, always a great adherent of mysticism and miracles, started a setting of ancient Chinese poetry rendered into German. The result was what Mahler called “probably the most personal composition I have created thus far.” These are songs of a desperate love of life, of existential loneliness, of death and leave-taking, but also of the certainty of another world we sense behind the visible one.

Symphonies No. 9 and 10

While Mahler’s physical strength was gradually ebbing, his creativity was reaching a final pinnacle. The Ninth Symphony was the only symphonic work of this size that Mahler completed in a single year – 1909. The introductory Andante is the most extraordinary piece of music that Mahler ever composed. The final, exhausted disintegration of the orchestra is followed by a reprise of the initial motifs in the brass and tympani, portents of disaster and death. Numerous notes in the draft of the score indicate that Mahler associated this work with memories and thoughts of parting: the first movement is inscribed with the words: “Oh days of youth! Vanished! Oh love! Scattered!”, and “Farewell!, Farewell!” Mahler did not live to hear his Ninth Symphony performed.

Mahler completed only drafts and sketches for his Tenth Symphony before his premature death at the age of 50.

Mahler’s Wife: Alma Mahler-Werfel

Alma Mahler-Werfel is one of the most fascinating as well as one the most controversial women of the 20th century. Her biography reads like a who’s who of intellectual life from turn-of-the-century Vienna to the years of exile in the US.

Born in Vienna in 1879 to the landscape painter Emil Jakob Schindler and the singer and actress Anna von Bergen, Alma became the stepdaughter of Carl Moll, one of the founders of Vienna’s Secession, after her father’s death in 1892. Following a two-year rapturous relationship with Gustav Klimt, she fell passionately in love with Alexander von Zemlinsky, with whom she studied musical composition. At the age of 23 she married Gustav Mahler, who was nearly 20 years her senior. Shortly before Mahler’s death she engaged in an affair with the architect Walter Gropius, later the founder of the Bauhaus, whom she married after Mahler died, and after she had pursued a tumultuous three-year sexual relationship with the painter Oskar Kokoschka. She deceived her second husband with the writer Franz Werfel, with whom she lived for ten years before they married. Together with Werfel she emigrated to the US in 1938. Thomas Mann described her during this period as “la Grande Veuve”, and the “Grand Widow” dedicated her years in exile to overseeing the musical legacy of Gustav Mahler and writing her autobiography, “And the Bridge is Love”. She died in New York in 1964 at the age of 85.

Alma Mahler-Werfel, whose hunger for socialising was legendary, maintained a “salon” in her villa in Vienna as well as at her summer retreat in the mountain resort of Semmering, and continued this tradition later in California and New York. Her circle of friends and acquaintances included the writers Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Gerhard Hauptmann, and the composers Hans Pfitzner, Alban Berg and Arnold Schoenberg. Ernst Krenek and Elias Canetti found her repugnant, and she engaged in intrigues against Wassily Kandinsky as well as Thomas Mann, who nevertheless held her in high esteem, and whose family members were frequent visitors to her home. The biologist Paul Kammerer, who had the habit of kissing his toads at public appearances, and who took his own life following a scandal, fell ardently in love with her, and in the final years of her life she and writer Friedrich Torberg corresponded extensively.

Rarely has a person been the subject of such conflicting judgements as Alma Mahler-Werfel. She herself left behind numerous contradictory accounts of events. Only with regard to her appearance and demeanour does there seem to be general consensus. Tall and attractive, she possessed a nearly magnetic allure that only few were able to resist. While Alma Mahler-Werfel always attracted strong men to whom she could subordinate herself, she quickly assumed the role of the caring mother, who tended to the needs of her “men-children” and blossomed when they were dependent on her support. Although she was married to two Jews and had numerous Jewish acquaintances, she became notorious for her many anti-Semitic slurs. Basically shy and, on top of this, extremely hard of hearing, she concealed her inhibitions behind an air of extreme self-confidence. She masked her tendency toward depression confidence. She masked her tendency toward depression confidence. She masked her tendency toward depression confidence. She masked her tendency toward depression confidence. She masked her tendency toward depression confidence. She masked her tendency toward depression confidence. She masked her tendency toward depression confidence. She masked her tendency toward depression confidence. She masked her tendency toward depression with socializing, absentmindedness and alcohol. In the soul of Alma Mahler-Werfel, passion and sensuality alternated with coldness and calculation, and she remarked repeatedly that her insides were void, and that she did not really care about anything or anyone.

Alma Mahler-Werfel was the muse to numerous artists. She attracted artistic creativity in an almost magical way, but it was also one of her outstanding characteristics that she spurred these artists to produce their very best work. However, there was always something that left her unfulfilled. In her youth Alma Mahler-Werfel received extensive musical training and composed a large body of works, only some of which have been preserved, before Gustav Mahler put an end to her musical activities when they were married. She complied with this prohibition, although she cultivated the legend of this composing ban throughout her whole life. And still, there seems to be no one less suited to sacrificing herself for the sake of others than Alma Mahler-Werfel, and perhaps this is the reason for the make- believe life that she constantly complained of having to lead.