Inhaltsverzeichnis

During their centuries-long domination of Europe, the Habsburgs proved to be not only passionate builders but also keen travelers–a fact that is manifested in the diversity of imperial structures all across Austria.

Whether in Graz, Innsbruck or Vienna: you encounter the legacy of Austria’s imperial past wherever you go in this country – but nowhere, of course, in such concentration as in the country’s capital, where you can sense this grand imperial atmosphere even when visiting one of the city’s many historic coffeehouses. The entire city centre is filled with traces of the imperial dynasty: the Augustinian Church on Josefsplatz was the venue for many Habsburg weddings, while the Imperial Crypt, beneath the Capuchin Church, served as the final resting place for the members of the House of Habsburg. Most visitors, however, are more attracted to the many magnificent palaces, such as the Baroque Schönbrunn Palace, which contains no fewer than 1,441 rooms.

Some 1.5 million visitors are drawn to the splendid salons and living quarters of the imperial family each year, but the elaborately laid-out grounds alone would be worth a visit. And the park attracts not only holiday guests; many Viennese also enjoy strolling through the gardens up to the elegant colonnade known as the Gloriette, where a coffeehouse offers stupendous views across the city, or spending a few hours at the world’s oldest zoo. The palace grounds are also where the annual summer concert of the Wiener Philharmoniker is held – an experience made unforgettable by the superb music and the sublime backdrop provided by the illuminated palace. And admission is free!

Imperial apartments can also be visited at the primary residence of the Habsburgs, Vienna’s Hofburg Palace. Particularly interesting insights into day-to-day imperial life are offered by the Silver Collection: the Habsburgs’ lavish dining culture alone illustrates what enormous expense was involved in running an imperial household of up to 5,000 people. The “Sisi Museum”, on the other hand, gives visitors a glimpse into the private life of the famous Empress Elisabeth. In addition to her dressing and exercise room, visitors can also view a reconstruction of the dress she wore on the eve of her wedding, her dressing gown and her death mask. These are all silent witnesses to a life that was ended tragically and violently with her assassination in 1898 – circumstances that undoubtedly contributed considerably to the “Sisi Myth”.

Considerably livelier is the ambience on the terraces of the former Festival Palace Hof, near the Danube River, when the Baroque Festivals held there transport the extravagant ‚joie de vivre‘ of that epoch to the present day. The opulent palace was originally built by the Habsburgs as a “princely reward” for Prince Eugene of Savoy to show their appreciation for his victory over the Ottomans at the Battle of Zenta in 1697. After years of decay and ruin, the palace was renovated at the turn of the millennium and restored to its original splendor.

Equally well preserved is the Imperial Villa in Bad Ischl, where the nobility spent their summers. As soon as the weather grew warm in Vienna, the Habsburgs escaped to the Salzkammergut – and everyone who could afford it followed their example. It all began in 1828 when the physician of the royal but childless couple Archduke Francis Charles Francis Charles Francis Charles Francis Charles Francis Charles Francis Charles Francis Charles Francis Charles and Princess Sophie of Bavaria advised them to visit the spa at the resort town to “take the waters”. The princess subsequently succeeded in bearing a child, who – as Emperor Francis Joseph – was himself to spend many summers at the Imperial Villa in Bad Ischl with his wife, Elisabeth. Today the Villa is open to the public and still retains the nineteenth-century ambience that was enjoyed by the emperor and his family. Even back in those days the Zauner bakery, an “Imperial and Royal Purveyor to the Court”, was pampering noble palates with its delectable cakes, and still today a visit to Bad Ischl would be unthinkable without a stopover at “Zauner”.

The Habsburgs established themselves in Tirol as well, but rather for political reasons than for relaxation and recreation: Emperor Maximilian I chose Innsbruck, the “Capital of the Alps”, as his residence because it was the ideal base for expanding his empire into what is now Western Europe. Today the legendary “Golden Roof” serves as a reminder of his reign: this loggia-like projection on the building’s second floor afforded a perfect view of the city’s main square and quickly became the symbol of Innsbruck. Maximilian’s Mausoleum, in the Hofkirche, is still considered one of the most important pieces of Renaissance in Central Europe. More of an insider’s tip is the Herzogshof in Graz, where the Habsburgs conducted their official business as sovereign princes of Styria: the building’s entire façade – over 220 square meters – was covered with murals on Greek-Roman mythological themes by the Baroque painter Johann Mayer. Whatever one might think of the Habsburgs, they certainly had exquisite taste, and one does not have to be a fan of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to take pleasure in their many cultural treasures.

The fascinating world of the Habsburgs

Vienna was the politically powerful and geographical center of Europe for five hundred years, just as long as the rule of the Habsburgs. With their palaces, government buildings and parks they left a substantial legacy in Vienna and the surrounding area. Under the family brand “Imperial Austria” this legacy is preserved and presented today in a timely manner.

The Imperial Apartments, the Sisi Museum and the Silver Room in the Vienna Hofburg, the UNESCO Cultural Heritage Schönbrunn Palace with its park and zoo, the Festival Palace Hof and the Court Furniture Depot provide fascinating insights into the multi-faceted history of the monarchy as well as the daily life at the imperial court with thematic walking tours, special exhibits, and individual focal points.

One of the main attractions of Vienna is the magnificent Ring Avenue with its huge building complex, the Hofburg. The imperial residence has undergone several expansions and revisions over the time and was the center of European power up to the beginning of the 20th century. It was from this palace that Emperor Franz Joseph, whose reign lasted 68 years, decided the fate of the Danube monarchy. The multinational state at the time was eight times as large as the present Austria.

With one single entrance ticket three different worlds of the Habsburg reign can be experienced: In the Imperial Apartments of the Hofburg, which nowadays houses the official offices of the Austrian Federal President, the Emperor’s family once spent the cold winter months. Today it is possible to visit the lodgings of the Kaiser and his wife Elisabeth (Sisy), which have been carefully maintained in their original state. Since time was a premium, also for rules of this period they also include semi-official rooms for audiences, conferences and offices. Two separate bedrooms reveal that at a certain point in time the legendary imperial couple no longer wished to share one bed. The beauty routine of Sisi, who was considered one of the most beautiful women, is reflected in her washroom and her exercise room. At the time it was considered revolutionary that an empress would have her own bathroom. Dining, taking tee, or eating breakfast took place in further chambers of the palace.

The immediately adjacent Sisi Museum is dedicated exclusively to the life and the legends surrounding the beautiful empress. After enjoying a free and unfettered childhood Sisy was made the fiancée of Kaiser Franz Joseph at 15. Later, at the court she resisted the required rigid rules of behavior and abhorred court intrigues. Her escape from these constraints took the form of a beauty and body cult that could hardly have been more extreme. After the suicide of her son she wore exclusively black. In 1898 she became the victim of an assassination. Her tragic and mythically exaggerated figure exudes to this day an ambivalent fascination. Among others, the legend is fortified by the “Sissi” film trilogy with Romy Schneider that is defined in the encyclopaedias as “regal kitsch” but is nevertheless so popular that it is shown on television every year at Christmas.

The Silver Chamber of the Hofburg displays a complete overview of the table manners and protocol of the monarchs. Numerous huge kitchen utensils are testimony to the amount of effort that went into cooking for 5,000 persons at the court. The craftsmanship of the royal purveyors by appointment is reflected in the delicate glass series, elaborately designed table service and silverware. Even the serviettes designed for festive meals can be admired. Some of the most exquisite pieces of tableware demonstrate that a gift of luxurious dining arrangements was common practice among rulers. Collecting porcelain was widely popular, whereby Asian objects were especially prized.

The most visited tourist attraction and true landmark of Vienna is Schönbrunn Palace. First erected as a hunting lodge with a large park, it was expanded to its present size from the middle of the 18th century and became the summer seat of the government and summer residence of the imperial family and the court. By the middle of the 19th century the palace and all auxiliary buildings were painted in “Schönbrunn yellow” that eventually became the trademark of the Habsburg monarchy. The entire ensemble with the palace, the park grounds with numerous fountains and statues, as well as the oldest still operating zoo in the world, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Through the widely branching rooms of the palace many walking tours, longer or shorter, are possible. One can see the private rooms as well as the more representative and elaborately appointed public rooms. Among these are the apartments of Emperor Franz Joseph and his wife Elisabeth (Sisi) from the second half of the 19th century as well as the splendid apartments of Empress Maria Theresa from the 18th century that were appointed in Rococo style one hundred years earlier. The impressive heart of the palace, the grand gallery, is transversed on every tour. This is where balls, receptions and other court functions took place. Every chamber, every hall of the palace can tell a story – about life style and philosophy of the time.

Our journey now takes us a few decades back from the Rococo to the Baroque. The festival palace Schloss Hof, a short hour’s journey from Vienna beckons us to this period in the history of art. The former festival palace is a matchless ensemble of magnificent architecture and master gardening. With fastidious attention to detail this Baroque synthesis of art gives a completely new and contemporary view into a bygone world. Schloss Hof was conceived as a retreat, representative hunting lodge and opulent location for large festivals. The renovation begun in 2002 is considered to be one of the most ambitious revitalisation projects in recent history. With the help of old plans, inventory lists and paintings, the original beauty of the palace and its accompanying dairy farm, a kind of self-sufficient agricultural facility, was restored. Plants and animals of the time were also brought back to life. Some of the species of flowers are more than 200 years old and the kept animals represent the favourite animal races of the Baroque such as white donkeys and Carinthian sheep. The interior rooms of the palace open new windows into the world of Baroque. The palace offers a unified impression of the life style of another era. To fully take in this experience you will need at least half of a day.

Wonderful insights into the history of domestic life at the court are presented by the Viennese Hofmobiliendepot (court furniture depot). Originally founded to store the furniture of Empress Maria Theresa, the Hofmobiliendepot has advanced to become the largest furniture collection in the world. The German name, incidentally, derives from the concept of mobility, “Mobilien,” as opposed to “Im-mobilien” referring to real estate, i.e. that which does not move. And, in fact, the furniture was moved when the Kaiser moved from his summer residence to his winter residence or when he traveled – the furniture traveled with him. The main emphasis of the collection is the former original pieces of the furniture of the Habsburgs from Schönbrunn palace, the Hofburg, Belvedere palace, Laxenburg palace and Schloss Hof. The collection not only gives us a unique perspective into the world of imperial furnishings but an overview of the development of Austrian furniture design in the 20th century with exponents by Roland Rainer, Franz West or Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky.

LINKS:

Kaiserappartements, Sisi Museum, Silberkammer

Schloss Schönbrunn with park

Tiergarten Schönbrunn (zoo)

Festschloss Hof (festival palace)

Hofmobiliendepot (court furniture depot)

Prince Eugene’s Winter Palais

Although Prince Eugene was only a commander of modest stature, his Palaces were all the bigger, grander and magnificent, with the palace in the Himmelpfortsgasse being the oldest.

When Prince Eugene of Savoy died in Vienna in 1736, he was the most influential and richest man in Europe. However, when he arrived here in 1683, he was destitute. He remained there for more than a decade as the Kaiser didn’t want to take him everywhere – there, Eugene could prove himself in battle and get wounded as much as he wanted to. It was not until 1697 when he banished the Turkish threat in Hungary that he could have his splendid palace built in the center of Vienna with the associated higher salary (critics claim that he obtained the Sultan’s war chest). The best architects of his time were just good enough for this purpose: Johann Fischer von Erlach and Lucas von Hildebrandt. The architectural result in 1700 was a sensation throughout Europe and guests came from all over to pay a courtesy visit to the Prince in his Winter Palace.

Since autumn 2013, the carefully restored palace in the Himmelpfortgasse is now fully accessible to the public for the first time. The Baroque staircase is impressive with its mighty Atlases and an awe-inspiring Hercules. The stately splendour continues in the chambers. The Golden Cabinet is – as the name suggests – skilfully decorated with gold on the ceiling, and mirrors enhance the dazzling splendour.

The Belvedere – the Prince’s Summer Palace during his lifetime – now one of the largest art collections in the country, uses the Winter Palace for temporary exhibitions of Austrian art in an international context. In addition, the large-scale paintings of the Savoy Prince in the hall of battle paintings can be admired. The centre of the hall has „The Battle of Turin“, not just an impressive testimony of historical accuracy, but also a fun picture puzzle: a restorer painted a cyclist into the tumult of the thousands of warriors, presumably for fun, at the end of the 19th century – and he did so even though, at the time of slaughter, 1706, the invention of the bicycle was still a long way off…

www.belvedere.at/de/schloss-und-museum/winterpalais

Cultural and Theme Routes

Roads used to be for the sole purpose of getting from A to B. Today one can experience all sorts of interesting and delightful things while “on the road” on one of Austria’s theme routes.

Admittedly, the Styrian wine roads have long ceased to be an insider’s tip. But there is a good reason for this: the charm of southern Styria, combined with the region’s outstanding wines and the hearty local fare, is something that truly must be seen – and especially tasted. No less pleasurable is a trip along the wine roads of Burgenland, where – in contrast to their Styrian counterparts – the red wines are predominant.

Anyone who prefers to bask in the atmosphere of past centuries should consider one of the many theme routes devoted to Austria’s colorful history. Along the Styrian Castle Route, for example, one finds a total of eighteen castles and palaces from various periods, strung together like pearls on a necklace. The reason for this great density of castles in a relatively small area is simple: the south-eastern section of Austria once lay at the edge of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, and these intimidating structures thus served as a bulwark against enemies from the east. And they accomplished this well: most of these castles and palaces never fell into enemy hands. One of these fortresses that resisted the invaders is the 850-year-old Riegersburg, which looms up from the edge of a 482-metre-high, steeply sloped volcanic cone like something right out of a fairy tale. Today an elevator takes visitors up to what was once known as the “strongest fortress in the Christian world”, and the castle gates are open to everyone. As is the case with so many of Austria’s castles and palaces, at the Riegersburg the past is brought to life through vivid and imaginative dramatizations. The witch’s exhibition with old instruments of torture, for example, is sure to send shivers down the spines of not only the youngest visitors. There are also historical re-enactments on Walpurgis Night, at the end of April, and on summer full-moon nights, events in which witches and sorcerers have center stage.

The Habsburgs’ nearly 600-year domination of Europe had less to do with magic than with political skill. Today one can retrace the imperial family’s footsteps on the “Route of Emperors and Kings”: this old “royal road” from Frankfurt am Main to Budapest leads through the former heartland of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and along the Danube, passing the Baroque palaces, monasteries and splendid residences of what were once mighty cultural and dynastic capitals. Travelers on this route make some surprising discoveries along the way: only very few people know, for instance, that the Habsburgs had no fewer than sixteen magnificent imperial rooms installed at the Augustinian Monastery of St. Florian, ensuring that the imperial family had a comfortable place to lay their heads during their journeys. And although Austria’s oldest city, Enns, is not nearly as well known as the imposing Benedictine Abbey at Melk, visitors are invariably enchanted by the medieval charm of its historic center. One travels even further back in time on the Transromanica, which follows the ancient Roman trade route from Germany via Austria to Portugal, or on the Via Claudia Augusta, the first real road to cross the Alps. It is fascinating to find out all the things people hauled across the mountains even back then, such as oil from Spain, Cretan wine, fresh oysters, and spices from Asia. By the way, some hosts and hostesses along the Via Claudia Augusta even offer their present-day guests the opportunity to sample “Roman cuisine”.

But not only Austria’s rulers have left their mark on this country: many Austrian theme routes are devoted to the traditional arts and crafts of the local people. Thus on the Wood Road, in the thickly-wooded Murau area of Styria, one learns about the significance of regional wood as a building and manufacturing material and as an energy supplier, as well as its use in the making of musical instruments and in the visual arts. In Vorarlberg’s Bregenzerwald the Cheese Road, which links Alpine dairies, farms, restaurants and cheese shops, tells the story of the centuries-old tradition of cheese-making. Whether one is interested in arts and crafts, the country’s history, its culinary delights, or all of these things, it is a good idea to allow plenty of time when exploring Austria’s theme routes. After all, sometimes an entire world can lie between A and B.

A Tour through Austria

Austrian cities are always good for a surprise, even if one visits them regularly.A tour of the country’s cultural sights promises an astounding variety of experiences, impressions and pleasures that could scarcely be more different from each other.

Vienna can boast two UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the historic city center and the Baroque ensemble of Schönbrunn Palace and its grounds. One can find art treasures and magnificent buildings all over the former imperial capital. The most important “cabinet of art” in the world, the Kunstkammer in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, takes visitors back in time to the Renaissance and Baroque ‚Kunst- und Wunderkammer‘ (chambers of arts and natural wonders) of the Habsburgs.

Austria’s youngest provincial capital, St. Pölten, can look back on a long history, with its town charter dating back to the twelfth century. One of the most striking features of the Lower Austrian capital today is its hypermodern government district, and directly adjacent is the equally modern cultural district with its futuristic Festspielhaus, where world-renowned musicians and dance companies perform regularly.

Linz, the capital of Upper Austria, is remarkable for the coexistence of traditional and contemporary architecture. This city, situated directly on the banks of the Danube, succeeds in blending art, science and technology to create an impressive synthesis. A host of modern buildings, such as the Ars Electronica Center, provide a stimulating contrast to the Baroque city center. The Lentos Kunstmuseum and the new Musiktheater are two other outstanding modern buildings and popular attractions for visitors to the city.

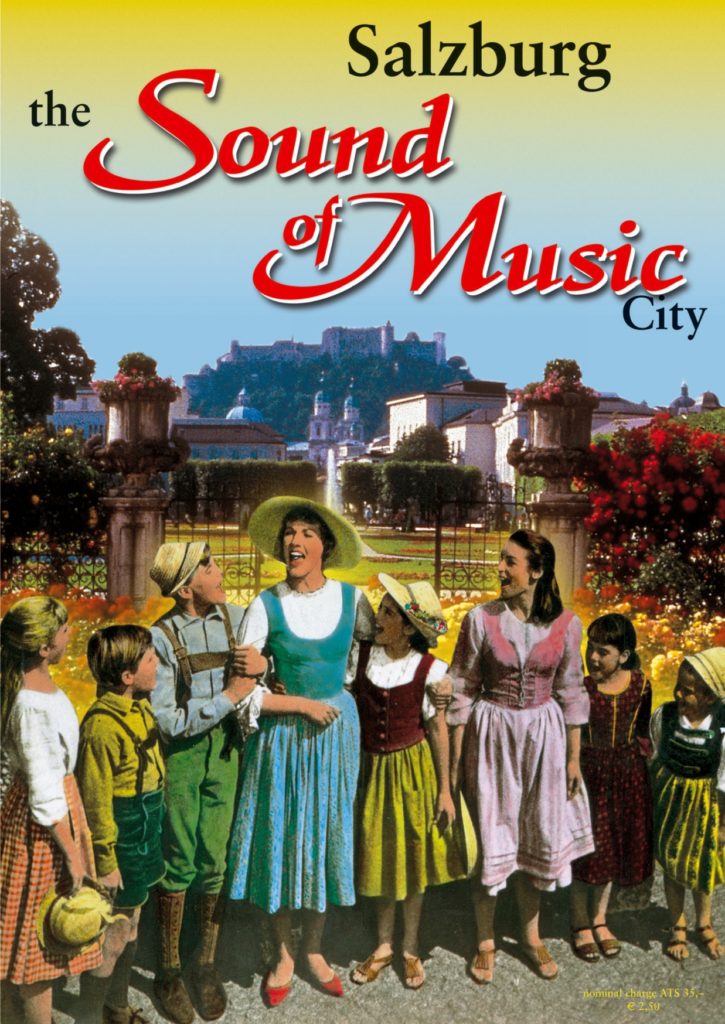

The Baroque city center of Salzburg, Mozart’s birthplace and home to the famous Salzburg Festival, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997. The cityscape is marked by numerous churches and palaces as well as the Baroque palaces of Mirabell and Hellbrunn. Salzburg Cathedral and the medieval Hohensalzburg Fortress are other architectural highlights. And visitors to Salzburg should not leave without taking some of the city’s sweetest souvenirs with them: the original Salzburg Mozartkugel.

What makes Innsbruck unique is not just its extraordinary location, surrounded by towering Alpine peaks. The Tirolean capital also features such world-famous sights as the Golden Roof (Goldenes Dachl), the art treasures in the Renaissance Ambras Castle, and the Court Church (Hofkirche). But the city also has its share of modern structures, including the Hungerburgbahn funicular railway and the Bergisel Ski Jump, both designed by the famous architect Zaha Hadid.

The history of Bregenz began as early as two thousand years ago, when a Roman settlement was located here. Today the main feature of the town center is the medieval St. Martin’s Tower, crowned by a sixteenth-century onion-shaped dome. The shoreline of Lake Constance is dotted with impressive modern buildings that represent a harmonious addition to the townscape: the Festspielhaus, the Kunsthaus and the new “vorarlberg museum”, which opened its doors in 2013.

It is the Carinthian capital’s Baroque and Jugendstil façades, lovely arcaded courtyards, and narrow passageways that lend the picturesque historic district of Klagenfurt its Mediterranean charm. The Jugendstil-era Stadttheater is not only the southernmost theater in the German-speaking world but also an architectural gem of extraordinary elegance.

Graz, Austria’s second-largest city, is home to two UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the old town, as the largest medieval historic district in all of Europe, and Eggenberg Palace. In 2011 the Styrian capital was also designated as a “UNESCO City of Design”, placing it among the world’s most creative and future-oriented cities. Architectural examples of this are the Kunsthaus and the Murinsel.

In Eisenstadt, the capital of the province of Burgenland, the visitor will encounter one name again and again: Joseph Haydn. The composer spent over forty years as music director in the service of the Esterházy Princes. Esterházy Palace, the city’s landmark, is the venue for concerts by world-class artists throughout the year. The scenic area surrounding the city is also well worth exploring: it is marked by extensive vineyards and features numerous wineries.

Jugendstil and modernity

At the beginning of the twentieth century Vienna was a European centre for applied arts, partly due to the Wiener Werkstätte, a workshop founded by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser following the model of the British “Arts and Crafts” movement.

The Wiener Werkstätte helped create an entirely new culture of taste, and its success led to the establishment of branches abroad (in the Czech cities of Karlovy Vary and Marianske Lazne, as well as in Zurich, New York, and Berlin). It was also in this period that artists of the Vienna Secession created their own t was also in this period that artists of the Vienna Secession created their own t was also in this period that artists of the Vienna Secession created their own t was also in this period that artists of the Vienna Secession created their own t was also in this period that artists of the Vienna Secession created their own t was also in this period that artists of the Vienna Secession created their own t was also in this period that artists of the Vienna Secession created their own distinctive Austrian version of the style known throughout Europe as “Art Nouveau”. In Austria it was called Jugendstil, and its most famous representative was Gustav Klimt.

Architecture with an International Flavor

Austria’s reputation as a nation with a great cultural tradition is due not only to its music, literature and art: this country also boasts many towering architectural achievements. As in every other artistic field, interaction and exchange with other cultures has always been crucial to the further development of Austria’s architecture.

The scene at the building site of Salzburg Cathedral in 1620 must have resembled a kind of Tower of Babel: there were local laborers, soldiers from all over Europe who had been separated from their units, and at the very center an Italian master builder who directed the entire project with great élan. Santino Solari was evidently a very busy man at that time: he not only oversaw the rebuilding of Salzburg Cathedral but was also charged with renovating the entire fortifications of the city. In the ensuing decades, many other Italian architects followed Solari’s lead and came here to lend Austria the Baroque splendor for which it is still famous today. In Vienna, Filiberto Lucchese worked on the church at Am Hof and on the Leopold Wing of the Hofburg, Carlo Antonio Carlone rebuilt Upper Austria’s St. Florian Monastery as a Baroque masterpiece, and Domenico Martinelli infused the Liechtenstein Garden Palace with splendour and dignity.

In the Baroque period, princes and bishops bought architects in much the same way as football clubs buy foreign players today, and building à la italianità was all the fashion. One builder who left a particularly enduring mark on Austria was the Genoa-born Johann Lucas von Hildebrandt. Hildebrandt came to the imperial capital in 1696 and went down in architectural history as the builder of Belvedere Palace, the Church of St. Peter, Schwarzenberg Palace, Laxenburg Palace, Hof Palace in Lower Austria, and Mirabell Palace in Salzburg.

This unparalleled cultural exchange can be attributed to the artistically-minded Emperors Leopold I, Joseph I and Charles IV, but they were motivated by concrete political interests as well: they were determined not to be outdone by the magnificent buildings of their French arch-rival Louis XIV, the Sun King, and thus had their own splendid Baroque prestige buildings, such as Schönbrunn Palace, erected. The Baroque unquestionably filled the veins of Austrian architecture with fresh blood. For too long, the country’s builders had worked in isolation, without permitting any Mediterranean influences to “flavor” their work. The Baroque era marked the beginning of a cultural exchange that also included new trends emanating from Austria.

With the advent of Viennese Classicism and the magnificent buildings commissioned by Empress Maria Theresa, Austrian architecture spread to the crown lands. Austria’s influence became even more significant in the second half of the nineteenth century: in the entire empire, now Austria-Hungary, the cities had begun to expand. Bit by bit, the city walls were razed, boulevards, plazas and squares were built, and new districts were made accessible to meet the housing needs of a growing urban population. And the model for this development was Vienna, where the splendor of the imperial capital was manifested in the Ringstrasse and its grand buildings. The most renowned architects in all of Europe were brought here by the Habsburg court, among them Gottfried Semper, who had previously worked in Dresden and Zurich, and Theophil Hansen, a Dane who had fell under the influence of Classical architecture while studying and working in Athens and came to incorporate Greek and Romans elements into his work. In this period, the cities of Prague, Brno, Cracow, Lviv, Trieste, Zagreb, Bratislava and Budapest were given a “makeover” as well – and everywhere the so-called “Francis Joseph Style” became established, with its enormous administrative buildings, museums, opera houses and concert halls.

An artistic style that originated in Vienna and came to have a considerable influence on Europe and even America was Jugendstil (1890–1910). Today, the floral style of Viennese Jugendstil can still be seen on some of the residential buildings lining the city’s Naschmarkt and on the Secession building with its characteristic gold dome.

Austria has experienced a remarkable architectural awakening in the past twenty years, and visitors can experience this as well when they visit futuristic buildings such as the Kunsthaus in Graz, the Lentos Museum and Ars Electronica Center in Linz, and the hypermodern government district in St. Pölten. The province of Vorarlberg has become a center for innovation as well as the source of a new style of timber architecture that has spread all over Europe, one that aims for a symbiosis with the surrounding landscape, with the history of the region, and with the identity of the region’s inhabitants. After all: “People do not exist to serve architecture – architecture exists to serve people”.

Plain Postmodernity – Austrian Architecture

In 1967 Austrian architect Hans Hollein published his creed under the title: “Everything Is Architecture”: architecture, he wrote, is no longer perceived as a separate art form in its own right but has blended with the culture of daily life within the given scenic and social context. Prophetic in its day, this formulation has long since become reality.

In terms of tangible history, Austria’s major architectural attractions are an open invitation to travel back through the ages. The country is strewn with castles, palaces and monasteries, silent witnesses to a colorful past, much of it moulded by ecclesiastical culture. The medieval centers of numerous small towns afford a vivid glimpse of daily life in bygone centuries. In Vienna, finally, the wealth of opulent public architecture testifies to the city’s erstwhile status as the capital of a vast empire.

Contemporary architecture in Austria will bear comparison with that in any other country. It is an indication of the country’s sense of style and the sensitivity with which its everyday culture has been moulded. The stylistic tendencies range from minimalism and reductionism to deconstructivism and are manifested in both public spaces (like Vienna’s Museum Quarter) and private buildings (like those commissioned by, for instance, young vintners or major business enterprises). At the same time Austria has long been a pioneer of ecological building. While the architectural themes may vary from province to province, the buildings in question share a common concern to relate to the natural surroundings and/or to the existing architecture. Burgenland’s summers are generally hot, its winters cold, which makes it an ideal wine-producing region. It is here that Austria’s most pungent reds and its sweetest white wines mature. Burgenland’s vintners (like the Esterházy Wine Estate) are making a name for themselves as progressive builders, by putting up exciting contemporary structures among the vineyards or commissioning sensitive refurbishments of and extensions to their wine estates. Carinthia with its mild southern climate and its invitingly warm bathing lakes looks back on a tradition of Mediterranean building styles. Lakeside villas and bathing huts emanate an old-world atmosphere.

Some of today’s building is on a more visionary scale, like Günter Domenig’s “Steinhaus” on the shore of Ossiacher See, a now famous example of postmodernist deconstructivist architecture. The Hypo-Alpe-Adria Bank Head Office, another deconstructivist design, radiates an open, visionary excitement. Lower Austria is a treasure trove of architectural discoveries, an intriguing juxtaposition of revitalized historic buildings, adapted edifices from the time of the industrial revolution, and contemporary architecture. A stroll through the Old Town of Krems can become a time warp to the Middle Ages, while the town’s Kunsthalle exhibition facility brings you right back into the present. Lower Austria’s most spectacular architectural gem is undoubtedly the Loisium, a sprawling multimedia wine museum with an adjoining designer hotel, the work of architect Steven Holl. Equally thrilling in its own way is Grafenegg’s “Cloud Tower”. By way of a contrast Equally thrilling in its own way is Grafenegg’s “Cloud Tower”. By way of a contrast with the palace building in the historical-eclectic style, the expressively folded Pavilion projects skywards, serving as a sculpture, an open-air stage and a recreational space in one. Throughout its history, from medieval times to the present day, Upper Austria has always produced outstanding architecture, as witnessed by the historic Old Towns of Wels, Steyr, Schärding, Gmunden and by a wealth of monasteries and fine old churches.

The province’s outstanding contemporary building is the Lentos Art Museum beside the Danube in Linz, an incisive building with clear-cut lines, a kind of larger-than-life 130-metre wide bridge harboring a space for art that reflects the waters of the Danube. Until Lentos was inaugurated in 2003, Linz’s Brucknerhaus, a concert facility with “floating” concert halls dating from the 1970s, was the first contemporary building of note in the Upper Austrian capital. Salzburg is widely associated with the term “Baroque” which is loosely applied to the sum total of churches, palaces and squares that Mozart knew in his native city.

Several outstanding examples of contemporary architecture document the other face of Salzburg and the way it perfectly supplements its historical legacy. One instance is the Museum of Modern Art on Mönchsberg, looming over the Old Town like the fortress of Hohensalzburg. Restrained and unfussy from the outside, it provides a generous space for the art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Styria harbours an exceptionally lively architectural scene to this day. What began in the 1960s as a rebellious generation of architecture students is now known as the “Graz School”, and the revolutionaries of yesteryear have long since turned into renowned architects and teachers. Günther Domenig holds a chair at Graz University, Michael Szyszkowitz teaches in Braunschweig, Manfred Wolf- Plottegg is a university professor in Vienna, Klaus Kada in Aachen. The latter recently caused a sensation with his imposing design of Graz’s Stadthalle. The spirit of the Graz School has spread to the city’s urban planners, which explains why the new Kunsthaus modern art facility designed by the British team Cook and Fournier is a planned vision that has taken on concrete shape. This building (familiarly dubbed “The Friendly Alien”) and Vito Acconci’s Island in the Mur are incontrovertible evidence that what architecture has hitherto dreamt of can be built. In recent years mountainous Vorarlberg has established itself as a Mecca for architecture enthusiasts. In the last four decades a wealth of fine functional buildings has gone up. Since the 1990s the European architectural community has started to take note of Vorarlberg.

A pioneer in the field of sustainable building, Vorarlberg has established a technical edge in the field. The most conspicuous features of contemporary building styles here are the rational use of resources, simple and constructively conceived ground plans and materials, and also a continuity that goes back directly to local traditions. The traditional buildings of the Bregenzerwald region are notable for their cautious use of the existing materials. Moreover, Vorarlberg’s architecture could not have got where it is today without craftsmen traditionally open to novel solutions. Technical innovations and sophisticated production processes have emerged as a result of the collaboration between design and crafts. Architecturally versed visitors never fail to marvel at the simple but perfected detailed solutions and the consummate skill evident in the working of wood. For several decades now Tirol’s neighbours in Vorarlberg have been demonstrating how appealing unfussy architecture can be. The Tyroleans have now caught the building fever. Given that Tyrol is known for its hospitality, most of the exciting new buildings here cater to the needs of visitors. One highlight is Zaha Hadid’s Bergisel ski jump, a futuristic structure that has come to be known as the “Innsbruck Lighthouse”. Visitors can go to the top of the tower to enjoy the superb view of the Inn Valley from the platform or the restaurant.

Further evidence of Tirol’s determination to foster contemporary architecture includes the new Hungerbergbahn mountain railway in Innsbruck, and the branches of the MPreis supermarket chain, which have gained numerous architectural awards. The nation’s capital, Vienna, has an almost unparalleled range of well- preserved historic buildings. This is a considerable challenge for contemporary architects, whose work has to stand side by side with history. That the city has mastered the leap into the twenty-first century with aplomb is testified by, for instance, the new Donau city Skyline and the Museum Quarter. A specifically Viennese aspect of architectural culture is the adaptation and enlargement of existing buildings. The resultant achievements in the field of interior architecture have made their mark worldwide.